The New Détente: Driving a Wedge Between Russia and China

By Sam Hagood, University of Chicago

Over a thousand days have passed since Putin sent his first troops into Ukraine. The Ukrainian conflict has since claimed the lives of millions; its hunger for materiel and men draws in superpowers and neighbors alike. Allies have shipped ammunition, adversaries have cried foul play, and the American-led international order has bent but not broken.

Into this fold march some 11,000 soldiers, picked up by Western intelligence over the last few months. They belong to Kim Jong Un, autocratic leader of North Korea and increasingly close confidante of Vladimir Putin. Kim’s forces appear to be headed for the Kursk region, where Ukraine recently broke through onto Russian land.[1]

On November 11, Kim signed a landmark mutual defense treaty between the DPRK and Russia, obliging both countries to use “all means” in defense of one another if either faces “aggression.”[2] When the agreement first reared its head in June, Kim’s troops trading fire with Ukrainians would have seemed a figment of the imagination. Now new questions press in, not least among them how the rising power in the East, China, will respond to Kim’s boldness.

This paper will argue that the United States should aim to reproduce with China the Cold War paradigm of détente. U.S. foreign policy can piece apart the China-Russia “no-limits” alliance through a careful alignment of incentives and obstacles for China. This paper will first examine the changing balance of power between China, Russia, and North Korea. Next, it will lay out a comprehensive case the U.S. can make to China, incentivizing diplomatic movement away from Russia and towards the U.S. The final section will examine the potential flaws of this strategy and what could come of its execution.

Shifts in a Trilateral Relationship: Russia, China, and North Korea

Relations between Moscow and Beijing have changed dramatically over the last few years. To begin, one must understand how drastically the war in Ukraine has altered the purposes and partnerships of the Russian economy. The Kremlin has ramped up defense spending in the face of sanctions, heavily subsidizing an increasingly non-diversified economy.[3] Human capital has fled beyond Russian borders in droves, and concerns about the postwar outlook of Russia’s non-diversified oligarchy abound. Russia’s saving grace remains the vast reserve of hydrocarbons dormant beneath her snowfields and highlands. Though customers like the EU have tightened their belts, Russia has found a willing recipient of energy exports in China.

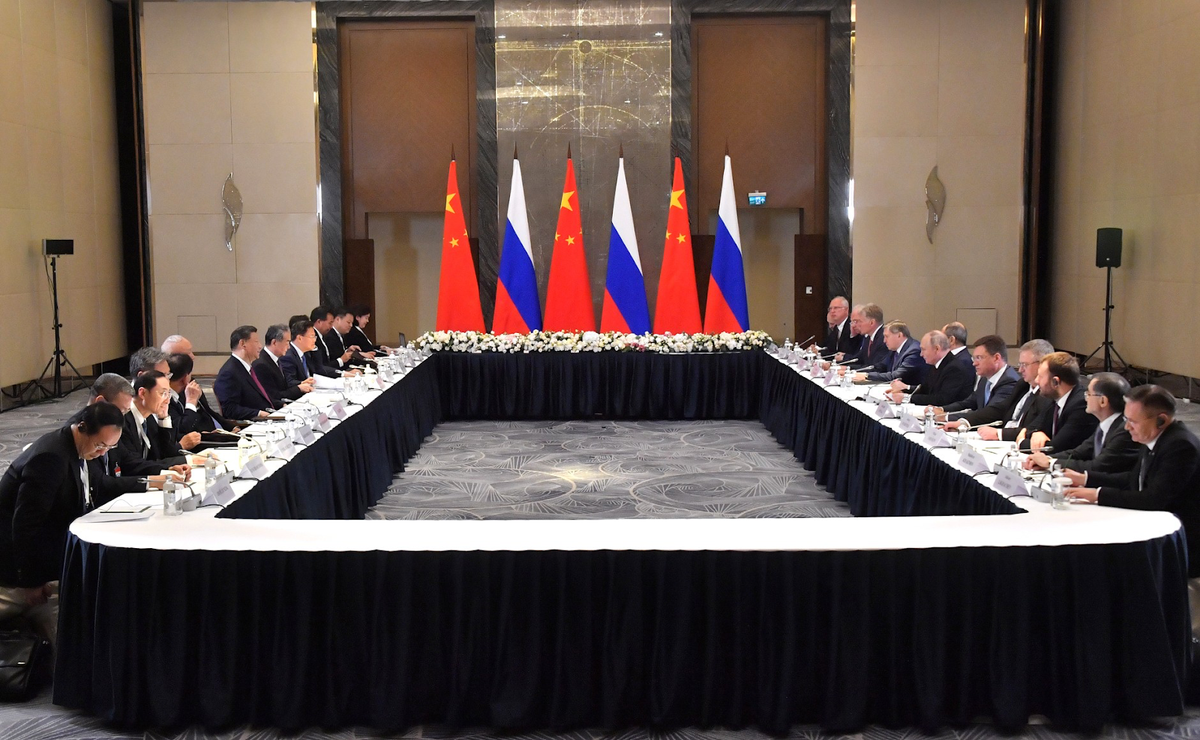

In the big picture, trade between the two countries grew by 30% to $190 billion in 2022 and by 26% to $240 billion in 2023.[4] Today, Russia is China’s largest oil supplier at 19% of total imports, sending 2.5 million barrels per day according to a March report.[5] Domestic factors have recently lessened Chinese demand, but the trend leaves Russia primarily indebted to two economic engines: the war in Ukraine and the Chinese demand for energy.[6] Xi Jinping understands this paradigm and has used it to secure oil discounts and assert hegemony over Putin. A ceasefire in Ukraine could collapse the Russian economy as it currently stands; more likely is the future in which Russia becomes a vassal state to China.

Sino-North Korean relations play a quieter but perhaps more crucial role in this Eastern triangle. Since Chinese troops flooded Korea in 1950 to prevent American domination, relations between the two have soured, with China’s rise to power and normalization contrasting the DPRK’s refusal to evolve. One exception to its general stagnation has been North Korea’s military development, with its 2006 testing of a nuclear weapon giving China pause enough to support sanctions against its neighbor. Yet China remains the northern nation’s dominant trade partner, accounting for nearly 90% of its imports and exports. Bilateral trade increased tenfold during the 21st century, though the aforementioned sanctions dimmed more recent figures.[7]

The power dynamic naturally leans towards the stronger China, but Kim Jong Un has recently pushed back against complete reliance on the Chinese behemoth. Meetings with Donald Trump during his first term showcase this curiosity, as do more frequent missile tests. Additionally, although alignment with Russia could be expected due to closer Sino-Russian relations, Kim’s pursuit of ties with Putin has irked the Chinese establishment. Given China’s close ties with the DPRK, North Korean troops in Ukraine may dilute Xi Jinping’s image as a third-party mediator for peace. Furthermore, the recalcitrant Chinese economy would hardly benefit from regional standoffs, with a South Korea worried about its northern neighbor gaining military know-how and Russian support.[8] China’s actions regarding North Korea will reflect its larger priorities across the region and the world, and North Korea remains far from indispensable in that wider calculus.

The final side of the triangle connects Russia and North Korea. Unlike China, these two outcasts share a key disadvantage. The global system, with the important exception of European energy markets, can and has survived without significant access to their economies; the same cannot be said about the second-largest economy in the world. Nations worldwide, including the United States, are intricately bound to the Chinese behemoth and vice versa. Thus Russia and North Korea have grown closer, with necessity drawing their shunned economies and opportunistic militaries into alignment. Before his soldiers ever left their barracks, Kim sent Russia millions of artillery shells along with ballistic missiles for use in the deadlocked invasion.[9] In exchange, Putin has supplied the DPRK with food for its citizens and imports for its weapons factories.[10] How the world faces Russia and North Korea dictates how they, in turn, face the world. China has not shouldered this particular struggle alongside them, and it shows.

Sociologist Aiden Foster-Carter, who has studied North Korea for decades, describes it as the “comrade from hell for both Russia and China.”[11] Kim Jong Un’s relevance is a testament to the sway even the smallest of nations can wield when it comes to a balance between two great powers; the Korean leader appears to have heeded Machiavelli and chosen to align, at least to a degree, with the weaker Russia.

This counterbalance against Chinese interests may not be of utmost concern to Xi, but it will matter. U.S. leadership should consider the advantages widening this trilateral rift could create. If Kim Jong Un becomes enough of a nuisance, he could inadvertently become the key to throwing the trilateral relationship between Russia, China, and North Korea into general chaos.

Why Détente Matters Today

In policy discussions, the word détente typically refers to the thawing of Cold War tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. The war in Vietnam and the economic cost of the nuclear race brought both to the negotiating table. China and the USSR would drift further and further apart throughout that period, and the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and Strategic Arms Limitations Talks were promising successes. Yet differing expectations would bring détente to an end by the time the USSR invaded Afghanistan in 1979.[12] How can a period of foreign policy that ultimately failed hold valuable lessons for the US today?

The Cold War involved nations, objectives, and chess pieces quite different from those of the 21st-century Sino-American relationship—yet commonality persists. Like the Cold War, our modern security paradigm has been shaped along its edges by proxy wars. The current American standoff with China has tested national ideologies just as its predecessor did, challenging domestic stability and international visions for world order. Finally, both situations have required their parties to reckon with the economic effects created by their security stances. If the United States is to make a case to China for a gradual shift away from its warring allies to the north, these factors must inform its every communique and policy, and they all find precedent in the period of détente.

A New Overture to China: Green Futures

First, the U.S. should seek to draw comparisons between its interest in creating a greener world and Russia’s callous dismissal of the climate issue. The most tempting economic offer that Russia can make to the PRC is cheap energy. Yet energy is not all that an import-reliant economy like China needs to address, even its most basic needs. Food security, for example, has been a trade policy focus of the PRC in recent years;[13] other top imports include machinery, semiconductors, and raw minerals.[14] And, as the gears of civilization grind on, the lion’s share of these trade priorities broach an issue that Russia remains unwilling to address: climate change.

A growing body of research explores the acceleratory effects of traditional agricultural and mining practices on climate change. Studies are increasingly conclusive that exploitation of such resources harms the planet, which all nations must share.[15] What is already quite clear, in contrast, is that the Kremlin does not take climate change seriously—a reality evinced by a lack of relevant policy and lethargic summit participation. Putin continues to hedge climate queries as his pipelines pump millions of barrels per day.[16] China is no saint when it comes to hydrocarbon consumption, but it is also the world’s largest producer of renewable energy. Additionally, its status as a net importer relying heavily on outside countries for food and minerals will force the PRC to take long-term threats to these imports into consideration. As practices that Russia abets begin to impact Chinese bottom lines, this ideological schism will make itself all the clearer.

In contrast to Russian negligence, the issue of climate policy constitutes one of the few bright spots of recent Sino-American cooperation. The U.S. has worked with China on multiple initiatives addressing climate change.[17] Chinese propaganda touts Xi’s goal of an “ecological civilization,” and the PRC’s ever-increasing renewables capacity trades reliance on Russian energy for green self-reliance. Changes in administration will surely affect the U.S. stance towards both China and the climate, but the U.S. still represents a far more willing partner than Russia in an existential battle against global warming.[18]

In this context, China’s role in supporting the Russian defense-industrial base through dual-use exports matters. Support for Putin’s invasion further disqualifies arguments for the value of cooperation with the PRC.[19] U.S. trade officials and diplomats must juxtapose an economically backward and stubborn Russia with an economically prescient and self-interested China. If they succeed, they could thaw critical channels between Washington and Beijing, perhaps even putting Moscow on ice in the process.

An Old Friend: Reconsidering North Korea

Second, the United States must emphasize the threat Kim Jong Un poses to regional and global stability. There is no question that Russia has proven a valuable ally to China. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine eats into Western resources, morale, and resolve. As China presses outwards against American hegemony, it has found in Russia a friendly state experienced in that struggle. Russia has provided China with the cheap energy it needs as it develops renewable alternatives and cares for its listing economy. These and a handful of other bases rationalize the Sino-Russian arrangement, at least in the short term.

However, the Chinese relationship with North Korea is far from necessary to Xi. North Korea first represented the PRC’s ability to stand up to American military might. A 1961 mutual defense and aid treaty binds the nations together, the only agreement of its kind for either—until Kim signed his defense treaty with Putin in November. This is the last in a long line of realignments Kim has carved out. Kim often responds to sanctions with missile launch tests. In 2023, North Korea abandoned its Comprehensive Military Agreement with South Korea, and the accelerated ballistic missile testing since then has worried Chinese national security officials. Finally, while the North Korean strongman hasn’t met with Xi Jinping since 2019, he has greeted Putin twice in the last year or so.[20]

During the 21st century, China has often used its position on the UN Security Council to frustrate Western attempts at increasing sanctions on North Korea. North Korea has been a thorn in America’s side, not in China’s—until now. China has historically feared what regime collapse in North Korea would entail: hundreds of thousands of refugees rushing the Chinese border. It also seeks to limit conventional and nuclear proliferation between the two halves of the peninsula (South Korea ranks among its top trade partners).[21] Most importantly, China is currently combating an economic slowdown that could turn disastrous if not managed properly.[22]

Amid this instability, Kim made the decision to send ten thousand-odd troops to an entirely different continent, embroiling his nation in a war against NATO. South Korea has consequently not ruled out shipping its own weapons directly to Ukraine, and the Korean Peninsula is now the most inflamed it has been in recent years.[23] All this transpires on the back porch of a China attempting to heal within and project without. The ally that Xi once tolerated and used to frighten the U.S. has called into question not only his status as a peacemaker in Ukraine and the Middle East but his sway over his closest allies. On a watchful international stage, displaying that level of weakness will prove anything but tenable. [24]

Though U.S.-China relations have declined over the past decade, the two now have common ground when it comes to reining in North Korea. Xi may figure that Putin can control Kim’s actions, but the entire Chinese system is predicated on centralized control. The PRC may be able to pursue less draconian relations further from home, but can they afford to let a nuclear neighbor take orders from an ally they ideally won’t need in 20 years’ time? U.S. diplomats owe it to their country and the world to ask their Chinese counterparts that question.

Winning the War in Ukraine

Lastly, the master stroke for the new détente must land in the place where this story began: Ukraine. The sides are fast approaching three years of grinding conflict, with little recent progress to show for it. American leaders must act decisively to snatch real victory from the jaws of defeat or even a Pyrrhic facsimile: they must use the end of the war in Ukraine to drive deep the wedge between Russia and China that has formed over the course of the conflict. The “no-limits” partnership that the two revisionist powers shook hands-on in 2022 has weathered the storm thus far. Its true test will come at the end of the war, and that test’s intensity will depend on how peace comes to pass.

Ukrainian President Zelenskyy has proposed a victory plan that he believes can bring a resoundingly positive end to the war. He calls for an influx of Western support and weaponry for the Ukrainian military, showing resolve and strength.[25]Biden’s go-ahead on long-range ATACMS missile strikes targeting “hundreds of known Russian military and paramilitary objects in Russia” represents an initial step in this direction.[26] Zelenskyy also asks for economic support in rebuilding his war-torn nation, citing its rich natural resources (grain, uranium, etc.) as a pivotal asset to whoever wins the war. Finally, he asks to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[27]

This plan has been criticized as an overextension of Western power and a dangerous step towards a continental war, tempting Russia to use its tactical nuclear arsenal. Yet the history of Putin’s conquest of former Russian territories is one of the U.S. standing by. When Russian troops invaded Georgia, when Crimea fell, when the future in Ukraine looked bleak, Western eyes turned blind. The United States needs to open its eyes and realize that defending Ukraine matters to the whole world, not just to Europe. The imperative emerges not only from the oft-ridiculed mandate to defend democracy worldwide. It also considers the fleeting opportunity to isolate Russia through a victorious peace, and the gamble turns on allowing Ukraine to join NATO after the war.

Putin gambled when he launched his invasion of eastern Ukraine. Thanks to European and American resolve, that gamble cost him dearly. He has supported his economy by shifting it to a wartime footing and sending nearly 40% of his budget to the frontlines, but the cracks continue to form. Ominously, many economists believe that the Russian economy will collapse soon after victory or defeat.[28] The massive cost of rebuilding a conquered Ukraine and the Russian interior, coupled with labor shortages and a non-diversified economy, may make victory as untenable as defeat. Thus, a more sinister threat remains: the possibility that 72-year-old Putin would continue to accelerate his timeline on returning states across Eastern Europe and along the Baltic to the fold of a revenant tsarist empire.[29] This is an unlikely worst-case scenario. In a more likely eventuality, the end to the conflict in Ukraine will spell disaster for the economic and hegemonic independence of the Russian state from China.

China reaps rewards from having Russia as a junior partner, but it hedges its bets by maintaining relations with the EU and America. If the West can end the war in Ukraine in such a way that China comes to realize no wager on Putin’s sinking ship will pay off, détente can be achieved. In lands far from the Pacific Ocean that the U.S. and China share, Russian ambitions have divided the two superpowers along a line that China doesn’t care about at its core.[30] Ukraine joining NATO would be the final vote of confidence by the West in defiance of Putin’s aggression, sending a warning all the way across Asia to the city of Beijing.[31] Atop this warning can ride the offer of peace through strength; peace, after all, is what China truly needs, if not what it wants. The choice is China’s to make, and that is where the first two prongs of the strategy must make their mark.

The United States can counter a violently nostalgic Russia most effectively by convincing China that an alliance with Russia will not secure Chinese aims. The most visceral evidence it can give for this thesis is a resounding victory in Ukraine. Given, the PRC and the United States have a litany of disagreements that will remain after this détente is accomplished, but such is the nature of international affairs. Russia will likely remain aligned with China, but its weakness will necessitate demotion from a future Sino-American negotiating table. Putin gambled; the West would be both bold and correct to gamble, in turn, that Xi Jinping has his own interests held closest to his heart.

What Lies Ahead

North Korea has offered the West a fleeting opportunity to disrupt the alignment between Russia and China. The divergence between the two on long-term economic philosophies, the incendiary of North Korean recklessness and diplomatic drift, and the prospect of victorious peace in Ukraine all support the possibility of drawing China away from Russia back towards the international order that has allowed it to grow strong. The PRC will be a testing and straining participant—but it will be a participant nonetheless.

Indeed, it must be emphasized that this détente would by no means bring a cease to strategic competition between China and the United States. It only seeks to unburden China of its unstable and conniving allies to its north. For China, this means the chance to regroup domestically; for the United States, the chance to refocus on the Indo-Pacific. The shift will ultimately favor the West, but it will also benefit China. In the end, the true game is whether China will commit to a step away from zero-sum statecraft or whether the PRC will take a win even if it means giving the U.S. a more significant one. If there are better angels beyond our borders, one must hope they play their part. Here, the charge is simply to the diplomats who speak for America, for you, and for me.

Notes

[1] Soo-Hyang Choi, “US Says North Korean Troops Are Engaged in Fight against Ukraine,” Bloomberg.com (Bloomberg, November 13, 2024), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-11-13/us-says-north-korean-troops-are-engaged-in-fight-against-ukraine?embedded-checkout=true.

[2] “North Korea Ratifies Landmark Mutual Defence Treaty with Russia,” Al Jazeera, November 12, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/11/12/north-korea-ratifies-landmark-mutual-defence-treaty-with-russia.

[3] Mary Glantz, “Ukraine War Takes a Toll on Russia,” United States Institute of Peace, March 11, 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/03/ukraine-war-takes-toll-russia.

[4] Robert Legvold, “The War in Ukraine in a Transitional World Order,” Ox.ac.uk, 2022, https://uc.web.ox.ac.uk/article/the-war-in-ukraine-in-a-transitional-world-order.

[5] Andrew Hayley, “RPT China’s Imports of Russian Oil near Record High in March,” Reuters, April 23, 2024, sec. Energy, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinas-imports-russian-oil-near-record-high-march-2024-04-20/.

[6] Chen Aizhu, “China’s July Oil Imports from Top Supplier Russia Fall 7.4% from a Year Ago,” Reuters, August 20, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinas-july-oil-imports-top-supplier-russia-fall-74-year-ago-2024-08-20/.

[7] Clara Fong and Eleanor Albert, “Understanding the China-North Korea Relationship,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 7, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-north-korea-relationship#chapter-title-0-3.

[8] Lee Gim Siong, “Boots on the Ground: China in a Spot as North Korea Marches into Russia’s War on Ukraine,” Channel News Asia, 2024, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/east-asia/china-north-korea-troops-russia-ukraine-proxy-conflict-4739991.

[9] Defense Intelligence Agency, “North Korea: Enabling Russian Missile Strikes against Ukraine” (Defense Intelligence Agency, May 2024), https://www.dia.mil/Portals/110/Documents/News/Military_Power_Publications/DPRK_Russia_NK_Enabling_Russian_Missile_Strikes_Against_Ukraine.pdf.

[10] Kim Arin, “Russia Sending North Korea Food in Return for Arms: Seoul Defense Chief,” The Korea Herald, February 27, 2024, https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20240227050728.

[11] Laura Bicker, “China Watching North Korea’s Friendship with Russia,” BBC, November 1, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c207gzprr33o.

[12] “Détente and Arms Control, 1969–1979,” Office of the Historian (U.S. Department of State, 2019), https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/detente.

[13] Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China Increasingly Relies on Imported Food. That’s a Problem.,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 25, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/article/china-increasingly-relies-imported-food-thats-problem.

[14] “OEC - China (CHN) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners,” Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2024, https://oec.world/en/profile/country/chn.

[15] William R. Sutton, “Climate Explainer: Food Security and Climate Change,” World Bank, October 17, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/10/17/what-you-need-to-know-about-food-security-and-climate-change.

[16] “Interview to China Media Group,” Office of the President of Russia (The Kremlin, October 16, 2023), http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/72508.

[17] Office of the Spokesperson, “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s,” United States Department of State, November 10, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-china-joint-glasgow-declaration-on-enhancing-climate-action-in-the-2020s/.

[18] Mikhail Korostikov, “Will Climate Change Drive a Wedge between Russia and China?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2023/12/will-climate-change-drive-a-wedge-between-russia-and-china?lang=en.

[19] Ellen Mitchell, “Ukraine Throws Wrench in Warming US-China Ties,” The Hill, April 28, 2024, https://thehill.com/policy/defense/4622615-us-china-ties-russia-ukraine-war/.

[20] Fong, “Understanding the China-North Korea Relationship.”

[21] Jennifer Lind, “Will Trump’s Hardball Tactics Work on China and North Korea?,” CNN, August 7, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/08/07/opinions/china-north-korea-opinion-lind/index.html.

[22] Lauren MacDonald, “China’s Economy Is in Deep Trouble,” American Enterprise Institute, July 16, 2024, https://www.aei.org/economics/chinas-economy-is-in-deep-trouble/.

[23] East Asia Division, “South Korea President Says ‘Not Ruling Out’ Direct Weapons to Ukraine,” Channel News Asia, 2024, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/east-asia/north-south-korea-president-yoon-suk-yeol-direct-weapons-ukraine-us-donald-trump-4732696.

[24] Lee, “Boots on the Ground.”

[25] Max Boot, “Zelenskyy’s ‘Victory Plan’ for Ukraine Makes Sense. It Has Little Chance of Being Implemented,” Council on Foreign Relations, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/zelenskyys-victory-plan-ukraine-makes-sense-it-has-little-chance-being-implemented.

[26] George Barros, “Interactive Map: Hundreds of Known Russian Military Objects Are in Range of ATACMS,” Institute for the Study of War, 2024, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/interactive-map-hundreds-known-russian-military-objects-are-range-atacms.

[27] Max Boot, “Zelenskyy’s ‘Victory Plan.’”

[28] Renaud Foucart, “Russia’s Economy Is Now Completely Driven by the War in Ukraine – It Cannot Afford to Lose, but nor Can It Afford to Win,” The Conversation, February 22, 2024, https://theconversation.com/russias-economy-is-now-completely-driven-by-the-war-in-ukraine-it-cannot-afford-to-lose-but-nor-can-it-afford-to-win-221333.

[29] Orlando Figes, “Putin Sees Himself as Part of the History of Russia’s Tsars—Including Their Imperialism,” Time, September 30, 2022, https://time.com/6218211/vladimir-putin-russian-tsars-imperialism/.

[30] Robert Legvold, “The War in Ukraine.”

[31] Nataliya Bugayova, “The High Price of Losing Ukraine: Part 2 -- the Military Threat and Beyond ,” Institute for the Study of War, 2023, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/high-price-losing-ukraine-part-2-%E2%80%94-military-threat-and-beyond.